The deeper story starts earlier: with First Nations plant knowledge, British naval hemp plans,

and overworked convicts digging at tired soil around Sydney Cove.This guide walks through that early cannabis history in a Q&A format, with

clickable sources so you can check claims for yourself or quote sections directly.

Did Aboriginal Australians traditionally use cannabis?

Short answer: current evidence says no.

Why do some people claim Aboriginal Australians used cannabis?

You’ll see big claims online:

- “Every ancient culture used cannabis.”

- “Aboriginal people smoked wild cannabis for ceremony.”

- “Cannabis is an ancient Dreaming plant.”

Those lines spread quickly on social media and in some cannabis marketing. But they tend to:

- Confuse cannabis with other native psychoactive plants

- Rely on guesswork, not on clear evidence

- Skip over serious research by archaeologists and anthropologists

If you check sources from places like the

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS)

or academic journals on ethnobotany, you will not find strong support for pre-contact cannabis use.

Is cannabis native to Australia?

No. Cannabis does not originate in Australia.

Most botanists and historians agree that:

- Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica evolved in Central and South Asia

- The plant spread along ancient trade routes to Europe, North Africa, and parts of the Middle East

You can see this outlined in general resources like the

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) short review of cannabis

and historical summaries tucked inside medical and botanical texts.

By contrast:

- There is no confirmed archaeological evidence of cannabis in Australia before 1788

- No securely dated cannabis pollen, seeds, or plant remains from pre-contact Aboriginal sites have been published in reputable journals

Aboriginal cultures worked with a huge range of native and introduced plants, but cannabis arrived very late in that story.

What psychoactive plants did Aboriginal peoples actually use?

The answer shifts by Country, language group, and local ecology. A few widely discussed examples include:

- Pituri (Duboisia hopwoodii and related species) – a nicotine-rich plant used as a

chewed stimulant, traded widely across central Australia.

The

Australian Museum’s pituri overview

gives a good short explanation. - Native tobaccos (Nicotiana species) – smoked or chewed, sometimes mixed with ash.

- A wide range of bush medicines – leaves, barks, resins, and roots used for pain, skin conditions,

respiratory issues, and spiritual healing. AIATSIS hosts broader context on Aboriginal health knowledge:

https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/health

.

These plants could change mood or alertness. But they are not cannabis, and Aboriginal people developed

their knowledge of them over tens of thousands of years, long before cannabis appeared on the continent.

Could cannabis have arrived with Macassan or other Asian visitors?

This is a fair question:

“If traders from Indonesia reached northern Australia, could they have brought cannabis too?”

We know that:

- Macassan trepangers from what is now Indonesia visited northern Australia to harvest trepang (sea cucumber)

- The

Australian Museum’s Macassan contact page

summarises this history clearly. - They traded tobacco, cloth, metal tools, and other goods with Yolŋu and neighbouring groups

Could cannabis have been in their cargo?

- In theory, yes.

- In practice, historians and archaeologists have not found strong proof that they traded cannabis into Aboriginal communities.

No clear signs appear in:

- Archaeological datasets

- Early written records by Europeans who documented Macassan influence

- Carefully recorded Yolŋu and other oral histories about Macassan visits, which researchers working with

AIATSIS and others have published

Most researchers therefore conclude:

Cannabis use in Aboriginal communities is a modern, colonial-era development, not a pre-contact tradition.

How did cannabis and hemp first reach Australia?

Who actually brought cannabis to Australian shores?

The plant arrived with the British, primarily as hemp for fibre.

When the First Fleet sailed in 1787–1788, the British government and the

Royal Navy

faced a strategic problem:

- They needed huge quantities of hemp for ropes, sails, and rigging.

- A lot of that hemp came from Russia.

- War or tension could cut supplies.

This pushed British planners to ask:

“Can we grow our own hemp in colonies like New South Wales?”

Did the First Fleet carry hemp seeds?

Evidence from colonial letters and reports held by the

National Archives of Australia

and the

UK National Archives

indicates that:

- Hemp and flax seeds were part of the agricultural supplies for the new convict colony.

- Early governors were instructed to experiment with hemp cultivation and report results.

- Officials looked for locations where hemp might grow at scale.

You can trace these themes across broader discussions of British imperial agriculture in resources from the

Royal Geographical Society

and in classic works on naval supply.

So cannabis first appears in Australian history as industrial hemp, not as a planned drug crop.

What exactly was “hemp” in early colonial Australia?

How did colonists use the term “hemp”?

In late 18th and 19th-century writing, “hemp” was a loose term. It often meant:

- Fibre crops suitable for rope and cloth, including Cannabis sativa.

- Sometimes other fibrous plants grown in different regions.

The primary concern for British planners in New South Wales was:

- Fibre strength and quality

- Yield per acre

- Suitability for naval rope and canvas

They cared far less about any mood-altering effects from the plants.

Hemp vs psychoactive cannabis: how do they differ?

Here’s a simple comparison that matches how modern law and science separate these forms:

Feature |

Hemp (fibre cannabis) |

Psychoactive cannabis (marijuana/hashish) |

|---|---|---|

Main use in 1700s–1800s |

Rope, sails, canvas, twine, paper |

Medicine, spiritual use, limited recreation |

Plant shape |

Tall, thin, long stalks, sparse leaves |

Shorter or bushier, many branches and flowers |

THC content (modern law) |

Usually |

Often > 5–20% THC |

Legal/social view |

Strategic crop for navy and shipping |

Gradually pulled into “dangerous drugs” policy |

Role in early Australia |

Experimental crop on convict and government farms |

Minor medical ingredient; rare evidence of recreational use |

For a modern technical overview, you can check the

World Health Organization’s cannabis background document

.

Key point: in early colonial New South Wales records, “hemp” means fibre almost every time.

Were convicts used to plant and process hemp?

Did early governors push hemp cultivation?

Yes. Several governors saw hemp as part of the long-term survival strategy and as a way to support British naval needs.

From surviving letters and reports, many of them accessible through

Trove and state archives:

- Governor Arthur Phillip (1788–1792) wrote about experiments with hemp and flax.

- Governor John Hunter (1795–1800) and Governor Philip Gidley King (1800–1806) continued trial plantings.

- British officials urged them to find sites where hemp could be grown at scale.

Convicts were the main labour force and were directed to:

- Clear land for hemp plots

- Plant and weed crops

- Harvest and process stalks for fibre

Why did hemp farming struggle?

On paper, hemp looked like a tidy answer. On the ground, it was far messier.

Historical sources and later analysis point to several recurring problems:

- Climate issues

European hemp strains were developed for milder summers and different daylight patterns.

New South Wales could be brutally hot and patchy in rainfall. - Soil conditions

Some early farms, such as at Parramatta, had thin or quickly exhausted soil.

Fertiliser options were limited, and intensive convict farming drained nutrients. - Competing priorities

Food shortages were a real threat. Wheat, maize, and vegetables had to come first.

Hemp for rope looked less urgent than bread on the table. - Limited expertise

Officers had notes from Britain but little practical knowledge for Australian conditions.

Mistakes in planting time and crop management were common. - Pests and disease

Local insects and plant pathogens caused damage that nobody fully understood at the time.

If you’re curious, search Trove for phrases such as “hemp cultivation” in early 1800s New South Wales:

https://trove.nla.gov.au.

Did any hemp schemes actually work?

To a limited degree, yes:

- Some plots produced usable fibre.

- Samples were shipped back to Britain for testing.

- Occasional reports praised the quality of Australian-grown hemp.

But these were small successes. Over the 19th century:

- Wool became the major export.

- Wheat and other grains were crucial to feeding the colony.

- Gold in the 1850s reshaped the economy.

Hemp stayed on the fringes and never became a central pillar of Australian agriculture.

Was cannabis used as a drug in the convict era?

Were convicts smoking cannabis for fun?

There is very little evidence of widespread recreational cannabis use in the early decades of the colony.

Early records – court documents, private letters, diaries – available through

Trove and collections at the

State Library of New South Wales – are full of:

- Rum and other spirits (and the chaos they caused)

- Tobacco use

- Fights, gambling, and general disorder

Cannabis barely appears at all as a social drug in those first generations. If a few individuals experimented,

they left very little trace in the surviving records.

How did cannabis enter colonial medicine?

The more visible path for cannabis in 19th-century Australia is medical.

A key figure is Dr William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, who worked in India for the British East India Company.

In the 1840s, he published reports on “Indian hemp” used to treat:

- Pain

- Muscle spasms

- Some seizure disorders

You can view a historical copy of his work through the

U.S. National Library of Medicine

.

His findings spread across the British Empire. By the mid–late 19th century, Australian doctors and pharmacists were:

- Importing cannabis tinctures and extracts from Britain and India.

- Listing cannabis preparations in pharmacy catalogues and medical guides.

Typical uses (by Victorian standards) included:

- Neuralgia and migraine

- Menstrual pain

- Insomnia and “nervousness”

- Certain muscle spasms and seizure-related conditions

These cannabis remedies sat alongside:

- Opium and laudanum

- Chloroform

- Chloral hydrate

- Coca-based tonics

For a modern scientific overview of medicinal effects and risks, see the

National Academies of Sciences report on cannabis and cannabinoids

.

How did newspapers and pharmacies describe cannabis in the 1800s?

What shows up in Trove?

If you search

Trove

for phrases like “Indian hemp” or “Cannabis Indica” in 19th-century Australian newspapers and journals, you’ll find:

- Medical case reports – describing treatment of pain, seizures, and other conditions,

and debating dose and side effects. - Pharmacy and trade listings – catalogues of imported drugs and chemicals that include cannabis preparations.

- Cautionary notes – warnings that cannabis should be used with care and can cause adverse reactions.

All this shows cannabis as a specialised medical tool, not a common social intoxicant.

Were authorities worried about cannabis abuse back then?

Public and political concern in 19th-century Australia centred on:

- Alcohol – especially the damage caused by cheap spirits and rum.

- Opium – regularly linked, in often racist terms, with Chinese communities.

Overviews from the

Australian Institute of Criminology

and documents in the

NSW State Archives

highlight how early drug laws focused first on opium and pharmacy controls.

Cannabis started to be folded into global drug policy debates in the early 20th century, through international agreements

overseen by bodies that later became the United Nations. You can read a short history on the

UNODC “early years of international drug control” page

.

How did cannabis later spread into Aboriginal communities?

This part belongs more to the 20th century, but many readers wonder about it after learning cannabis was not a traditional plant.

Is cannabis a traditional Aboriginal drug?

No. Cannabis is a post-contact plant in Aboriginal communities.

Its spread is tied to:

- Colonisation and dispossession

- Movement onto missions, reserves, and settlements

- Disruption of traditional economies and law

- Later growth of black-market drug supply networks

Alcohol policies also shaped patterns of use. In some regions:

- Alcohol was tightly restricted or banned.

- Cannabis sometimes became a substitute because it was easier to move quietly.

For broader data on drug use patterns in Australia, see the

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s alcohol and other drugs portal

.

What kinds of impacts were reported?

From the late 20th century, research and community accounts in areas such as Central Australia described:

- Regular cannabis use among some young people.

- Links to poor school attendance, mental health issues, and family conflict.

Aboriginal leaders and health workers often describe cannabis-related harm as one more weight added to:

- Grief from removals and massacres.

- Loss of Country and language.

- Poverty, overcrowding, and lack of opportunity.

The key historical point is simple:

Cannabis use in Aboriginal communities is a modern story layered over colonisation,

not a feature of ancient plant practice.

What are some common myths about early cannabis in Australia?

Myth 1: “Aboriginal people smoked cannabis for thousands of years.”

Evidence: none from secure archaeological or early ethnographic sources.

Reality:

- Cannabis evolved in Central and South Asia, not in Australia.

- There is no confirmed pre-1788 cannabis in Australian digs.

- Aboriginal plant traditions focus on species like pituri and native tobaccos instead.

Verdict: False. Linking cannabis to Aboriginal tradition this way ignores plant science and First Nations history.

Myth 2: “The First Fleet brought weed for convicts to smoke.”

Evidence: official letters talk about hemp for naval fibre, not for getting convicts high.

Reality:

- Hemp seeds came as part of a naval supply strategy.

- The goal was rope and sails for the British fleet.

- Alcohol and tobacco were the main psychoactive substances in early Sydney.

Verdict: Misleading. Cannabis seeds came with the First Fleet, but as hemp, not as a planned intoxicant.

Myth 3: “Hemp was a cornerstone of the early Australian economy.”

Evidence: economic histories from bodies such as the

Reserve Bank of Australia

emphasise wool, wheat, and gold, not hemp.

Reality:

- Hemp trials produced limited fibre.

- The crop faced soil and climate challenges.

- It remained minor compared with other commodities.

Verdict: Overstated. Hemp was an imperial experiment, not a founding industry.

Myth 4: “Cannabis only arrived with hippies in the 1960s.”

Evidence: Trove and medical archives show cannabis tinctures in use during the 19th century.

Reality:

- Medical cannabis existed in Australia by the mid-1800s.

- Recreational cannabis use grew strongly from the 1960s onward.

- Police and legal histories from the

Australian Institute of Criminology

document those later patterns.

Verdict: Partly false. The 1960s–70s were a turning point for recreational culture,

but cannabis as a plant and medicine had been present long before.

Quick checklist: how can you test cannabis history claims?

With so many memes, marketing pitches, and agenda-driven posts around drugs, a simple checklist helps you sort claims.

Question to ask |

Why it matters |

|---|---|

1. Who is saying it? |

Check if it’s a scholar, journalist, marketer, or fan site. |

2. Are dates and places specific? |

Vague “ancient times” often signal weak evidence. |

3. Are primary sources named? |

Look for archives, laws, medical texts, not just recycled blog posts. |

4. Is archaeology mentioned? |

Pollen, seeds, and artefacts carry real weight. |

5. Is there consensus in academic work? |

Compare claims with books and articles from historians and scientists. |

6. Is someone selling a product or cause? |

Commercial or political goals can bend stories. |

If a story claims cannabis has always been central to every culture, treat it as something to check, not a fact.

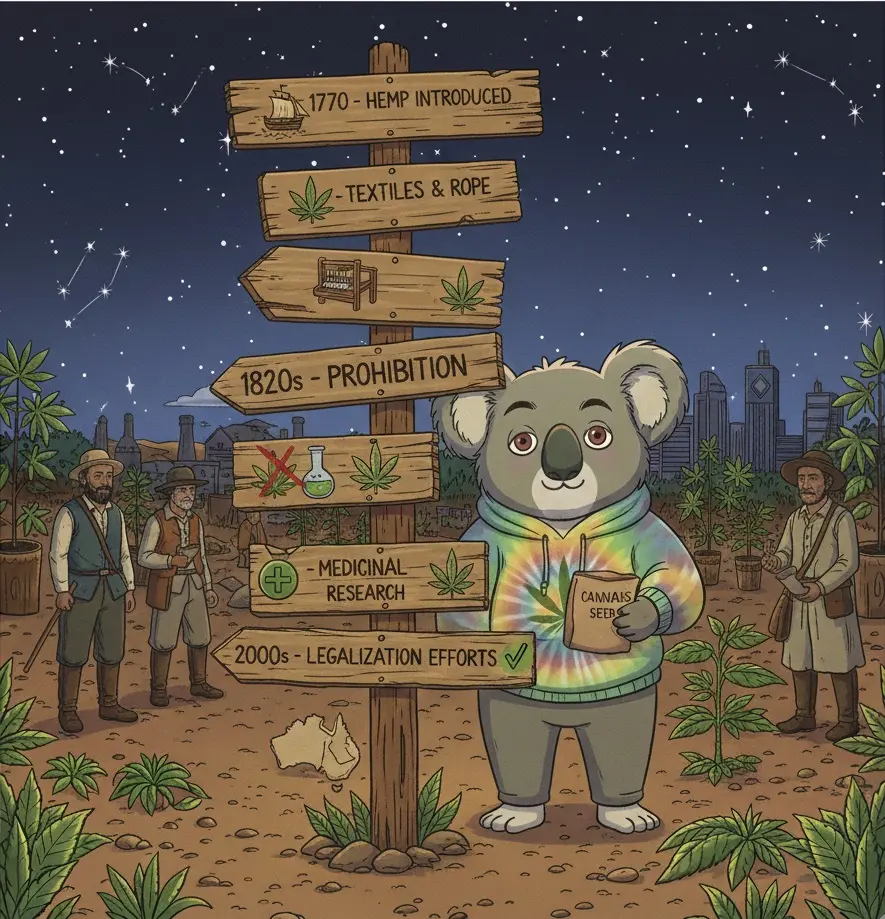

Short timeline: cannabis and hemp in early Australia

Here’s a simple timeline you can quote or share.

Period / Year |

Event or trend |

|---|---|

Pre–1788 |

No solid evidence of cannabis in Australia; rich Aboriginal plant traditions based on other species. |

1600s–1700s |

Macassan visits; tobacco and other goods traded; no clear evidence of cannabis. |

1787–1788 |

First Fleet sails; hemp and flax seeds carried for crop trials. |

Late 1780s–1790s |

Early hemp experiments near Sydney and Parramatta. |

Early 1800s |

Ongoing small hemp trials; problems with climate and soil. |

Mid–1800s |

Medical cannabis tinctures imported via Britain and India. |

Late 1800s |

Cannabis listed in pharmacy texts; occasional medical reports in newspapers. |

Early 1900s |

Cannabis begins to enter international drug control debates. |

1920s–1930s |

Australian states adopt stronger drug laws; cannabis gradually included. |

1960s–1970s |

Recreational cannabis use spreads; youth and counterculture scenes grow. |

2016 |

Australia establishes a legal pathway for prescribed medicinal cannabis. |

For official outlines of modern medical cannabis regulation, see the

Australian Government Office of Drug Control medicinal cannabis guidance

.

Why does this early history matter for today’s debates?

How does this affect conversations around legalisation and culture?

Modern debates over decriminalisation, medical access, and commercial hemp or cannabis industries often lean on history.

You might hear:

- “Cannabis is native to this land.”

- “Hemp built the early colony.”

- “Everything was legal and natural before prohibition.”

Careful use of sources such as

Trove,

state archives,

and peer‑reviewed research helps you:

- Correct friendly but inaccurate stories.

- Avoid using Aboriginal culture as a marketing hook for modern cannabis products.

- Recognise that:

- Hemp was a British imperial naval project.

- Medical cannabis arrived through colonial medicine and trade.

- Present-day recreational cannabis culture is much more recent.

How can you talk about this topic in a respectful way?

A few practical suggestions:

- Separate cannabis from Aboriginal tradition.

Acknowledge that First Nations plant knowledge is deep and sophisticated, but cannabis is a late addition brought by colonisation. - Name the impacts of colonisation.

Later cannabis problems in Aboriginal communities sit on top of land theft, violence, forced removals, and policy-driven disadvantage. - Avoid turning convicts into romantic weed farmers.

Hemp work was forced labour in harsh conditions, for a crop that often disappointed imperial expectations. - Use sources you can show others.

Point people to:- Trove articles

- Government and archive sites such as the

National Archives of Australia

and

State Library of New South Wales - Books and articles from serious historians and medical researchers

A grounded example

Picture someone researching a convict ancestor in New South Wales. They find an 1820s note in Trove about “hemp trials on

government land” close to where that ancestor lived. It is tempting to tell friends:

“My ancestor was one of Australia’s first cannabis growers.”

But after cross-checking with the

NSW State Archives

and local histories, they discover:

- The hemp crop was imposed by authorities as part of an imperial plan.

- Yields were poor, and the scheme never took off.

- The ancestor’s real daily stress centred on food, punishment, and survival, not on rope fibre.

The story is still interesting, but now it:

- Matches the evidence better.

- Shows the grind and control of convict life.

- Avoids slipping into cheerful myth-making.

Key facts about cannabis history in Australia

To close, here are the main points in a quick, quotable list.

- Cannabis is not native to Australia.

Science and archaeology show no solid evidence of pre-contact cannabis on the continent. - Aboriginal plant traditions centre on other species.

These include pituri, native tobaccos, and extensive bush medicines, documented by institutions such as

AIATSIS and the

Australian Museum. - The British brought hemp seeds with the First Fleet.

The goal was naval fibre for ropes and sails, not recreational drug use. - Convicts laboured on hemp trials, but the crop never became a major industry.

Poor soil, climate challenges, pests, and urgent food needs kept hemp on the margins. - Medical cannabis reached Australia in the 19th century.

Imported tinctures were used for pain and nervous conditions, influenced by work such as O’Shaughnessy’s Indian research. - Recreational cannabis use grew much later, especially from the 1960s.

That story links to youth culture, global trends, and changing drug laws. - Cannabis use in Aboriginal communities is a modern, colonial-era issue.

It is best discussed in the context of dispossession, trauma, poverty, and present-day social conditions.

Sources & References (clickable)

- Trove – National Library of Australia (digitised newspapers and journals)

https://trove.nla.gov.au - National Archives of Australia – colonial correspondence and official records

https://www.naa.gov.au - State Library of New South Wales – early colonial manuscripts and images

https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au - NSW State Archives and Records – colonial government documents, including land and farming

https://www.records.nsw.gov.au - Australian Museum – Macassan contact with Aboriginal Australia

https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/atsi-collection/macassan-contact/

- Australian Museum – Pituri overview

https://australian.museum/learn/cultures/atsi-collection/pituri/

- AIATSIS – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander resources

https://aiatsis.gov.au - Australian Institute of Criminology – drug law and policy research

https://www.aic.gov.au - Australian Institute of Health and Welfare – alcohol, tobacco & other drugs

https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/behaviours-risk-factors/alcohol

- Australian Government Office of Drug Control – medicinal cannabis guidance

https://www.odc.gov.au/medicinal-cannabis-guidance-documents

- UNODC – Early years of international drug control

https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/early_years_of_international_drug_control.html

- National Academies of Sciences – Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/24625/the-health-effects-of-cannabis-and-cannabinoids

- U.S. National Library of Medicine – O’Shaughnessy’s Indian hemp paper (historical)

https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101172107-bk

- Reserve Bank of Australia – Economic history of Australia

https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/economic-history-of-australia.html